Traditional implementations of state machines suffer from various problems including intermingled state handling, which lead to messy code that is hard to understand and maintain. Using features of the Go language allows for the elimination of these problems and improves the clarity of the code.

In this article, I will present the implementation of a lexer for a very basic language using a functional state machine. It will be able to parse basic expressions like 123 + 345 and double-quoted strings.

The lexer’s task is to read input from a Reader (the "program") and send appropriate descriptive "tokens" into an output channel. In an interpreter or compiler implementation, these tokens would then be processed by a parser.

The full example source code presented here is available on GitHub.

Let's first implement the core function of our lexer's state machine using the traditional approach:

func TokensTraditional(r io.Reader, ch chan<- Token) {

bufR := bufio.NewReader(r)

for {

c, _, err := bufR.ReadRune()

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

panic(err)

}

break

}

switch c {

case '+':

ch <- makeToken(Plus, "+")

case '-':

ch <- makeToken(Minus, "-")

}

}

}

Here we use a loop to read the sequence of runes from the Reader, then we look at each rune and send tokens of various types into the output channel.

To simplify these examples, we just ignore any unknown runes (whitespace etc.) We also just panic in case of errors.

So far, this is just a simple loop, not a state machine – there is no state to keep track of. This changes when we introduce something more complex.

Let's add code to parse integers:

func TokensTraditional(r io.Reader, ch chan<- Token) {

inInt := false

intBuf := strings.Builder{}

bufR := bufio.NewReader(r)

for {

c, _, err := bufR.ReadRune()

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

panic(err)

}

if inInt {

ch <- makeToken(Int, intBuf.String())

}

break

}

if inInt {

if isDigit(c) {

intBuf.WriteRune(c)

continue

}

ch <- makeToken(Int, intBuf.String())

inInt = false

intBuf.Reset()

}

if isDigit(c) {

inInt = true

intBuf.WriteRune(c)

continue

}

switch c {

case '+':

ch <- makeToken(Plus, "+")

case '-':

ch <- makeToken(Minus, "-")

}

}

}

The occurrence of a digit marks the start of an integer, which of course can consist of multiple digits. Since we are parsing runes one at a time, we need to keep track of the fact that we are "inside" an integer (using inInt.) At the same time, we buffer all of the integer's runes (into intBuf.)

The first rune that is not a digit marks the start of something else. This is our signal to send a new token using the contents of intBuf.

Notice that there are two locations where we are sending an "integer" token: 1. once during normal parsing, and 2. once when we encounter EOF. This is due to the fact that the input can end with an integer, and we need to flush our internal intBuf buffer.

Let's keep going and add one more step.

To parse strings, we need to add some more code to our state machine:

func TokensTraditional(r io.Reader, ch chan<- Token) {

inInt := false

intBuf := strings.Builder{}

inString := false

stringBuf := strings.Builder{}

bufR := bufio.NewReader(r)

for {

c, _, err := bufR.ReadRune()

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

panic(err)

}

if inInt {

ch <- makeToken(Int, intBuf.String())

}

if inString {

panic(errors.New("string not closed"))

}

break

}

if inInt {

if isDigit(c) {

intBuf.WriteRune(c)

continue

}

ch <- makeToken(Int, intBuf.String())

inInt = false

intBuf.Reset()

}

if inString {

if c != '"' {

stringBuf.WriteRune(c)

continue

}

ch <- makeToken(String, stringBuf.String())

inString = false

stringBuf.Reset()

continue

}

if isDigit(c) {

inInt = true

intBuf.WriteRune(c)

continue

}

switch c {

case '+':

ch <- makeToken(Plus, "+")

case '-':

ch <- makeToken(Minus, "-")

case '"':

inString = true

}

}

}

Parsing strings is basically the same as parsing integers, except that strings are always enclosed in double quotes. When parsing strings, we just ignore the quotes and do not include them with our tokens.

Our state machine now basically has three modes of operation:

While this whole example is a bit contrived, you may already be starting to see the following problems:

switch block.The larger the state machine gets, i.e. the more states we add, the messier it will become. Is there a better way?

In a word: Yes. In Go, functions are first class objects. This and the fact that Go also has closures can be used to our advantage. We will also make use of the defer statement later on.

Let's rewrite the state machine's core function:

func TokensFunctional(r io.Reader, ch chan<- Token) {

bufR := bufio.NewReader(r)

state := parse

for state != nil {

state = state(bufR, ch)

}

}

That’s it.

The function first defines a starting state of parse. Then it simply loops until we reach a nil state, which breaks the loop. The state itself is a function that is called in every iteration of the loop.

So how does this work?

The functional state machine uses multiple "state functions" that all match the following type:

type stateFunc func(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc

The type stateFunc is defined as a function that takes a Reader and an output channel (just like before), but also returns a new stateFunc. Now, this new stateFunc is the state to be executed after the current function is done.

The task of a state function is to parse accordingly (parse an integer, for example) or delegate to other state functions by returning an appropriate stateFunc.

We also need to set a rule: Whenever a state function is to be executed, the Reader's buffer cursor always needs to be exactly before the thing to be parsed. For example, if the state function to parse an integer is to be executed, the cursor has to be before that integer, i.e. the first digit still needs to be in the buffer.

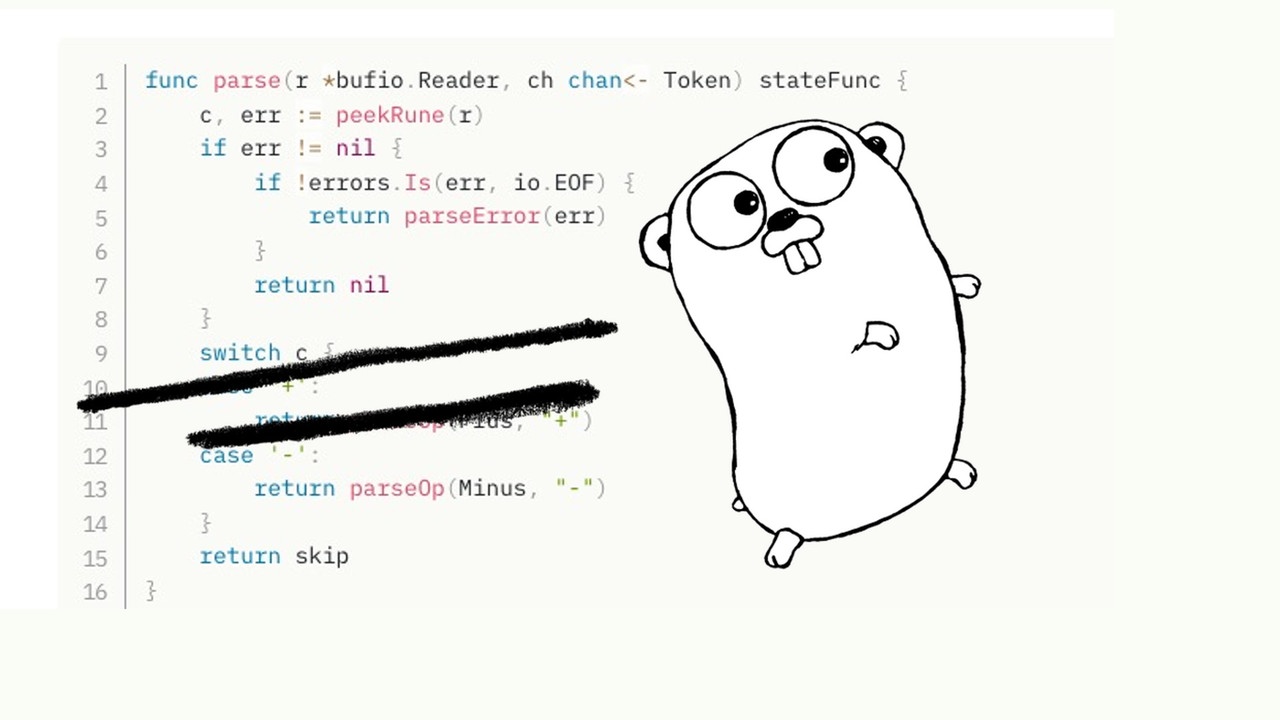

Let's see all of this in action by implementing the main state function to parse operators:

func parse(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

c, err := peekRune(r)

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

return parseError(err)

}

return nil

}

switch c {

case '+':

if _, _, err := r.ReadRune(); err != nil {

return parseError(err)

}

ch <- makeToken(Plus, "+")

return parse

case '-':

if _, _, err := r.ReadRune(); err != nil {

return parseError(err)

}

ch <- makeToken(Minus, "-")

return parse

}

return skip

}

The function first peeks at the next rune in the Reader. This will keep it in the buffer.

If we reach EOF, we just return nil, which stops the state machine loop.

Then, it checks which rune it has just peeked. If it is an operator it recognizes, it actually reads the rune from the Reader (now consuming it) and sends a token into the output channel. Finally, it returns parse as the state function that should be executed next.

If it doesn't recognize the rune, it returns skip as the next state function:

func skip(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

if _, _, err := r.ReadRune(); err != nil {

return parseError(err)

}

return parse

}

skip simply reads the next rune from the Reader, sends no tokens into the output channel, and again returns parse as the next state function.

We will learn about parseError later.

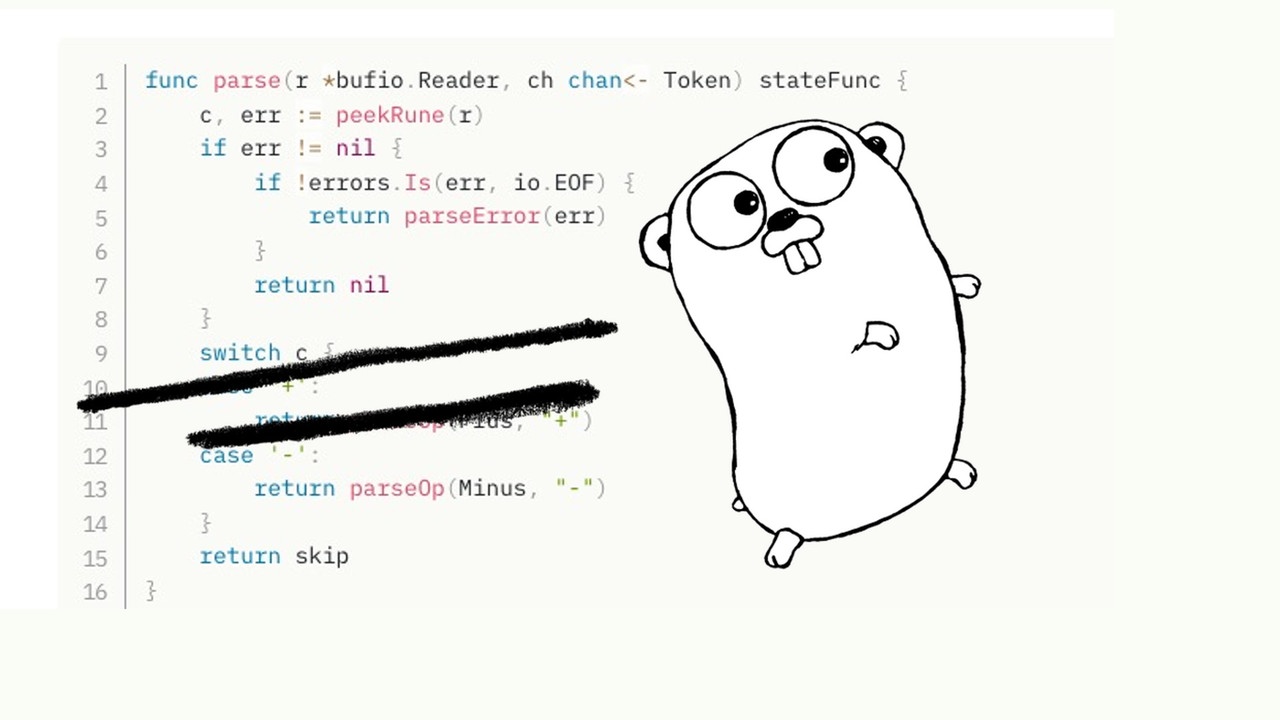

We can now make parsing operators a bit simpler:

func parse(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

c, err := peekRune(r)

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

return parseError(err)

}

return nil

}

switch c {

case '+':

return parseOp(Plus, "+")

case '-':

return parseOp(Minus, "-")

}

return skip

}

func parseOp(typ string, literal string) stateFunc {

return func(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

if _, _, err := r.ReadRune(); err != nil {

return parseError(err)

}

ch <- makeToken(typ, literal)

return parse

}

}

parseOp is a "constructor" function that returns a stateFunc. The beauty here is that inside the anonymous state function returned by parseOp, we have access to the arguments passed to parseOp (a closure.) This way, the function returned by parseOp can be parameterized.

The returned state function again consumes a rune, then sends a token into the output channel, and returns parse as the next state function.

The consumed rune is ignored (just as before.) Then the token sent is parameterized by the arguments passed to parseOp.

Notice that the state "parse an operator" of the state machine now has an actual name: parseOp.

To parse integers, we delegate to a new state function:

func parse(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

c, err := peekRune(r)

if err != nil {

if !errors.Is(err, io.EOF) {

return parseError(err)

}

return nil

}

if isDigit(c) {

return parseInt

}

switch c {

case '+':

return parseOp(Plus, "+")

case '-':

return parseOp(Minus, "-")

}

return skip

}

func parseInt(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

buf := strings.Builder{}

defer emitBuffer(ch, Int, &buf)

parseRune := func(c rune, eof bool, stop func(next stateFunc)) {

if eof {

stop(nil)

return

}

if !isDigit(c) {

r.UnreadRune()

stop(parse)

return

}

buf.WriteRune(c)

}

return forRunes(r, parseRune)

}

There is quite a bit going on here, so let's break it down.

First, the function sets up a buffer into which to parse the integer's digits.

Second, it sets up a defer call to send a token into the output channel when the integer has been parsed completely:

func emitBuffer(ch chan<- Token, typ string, buf *strings.Builder) {

ch <- makeToken(typ, buf.String())

}

It then constructs a new anonymous function that matches the runeFunc type:

type runeFunc func(c rune, eof bool, stop func(next stateFunc))The rune function is called for each new rune consumed from the Reader. It is also called once again when EOF is reached. In addition, it is passed a stop function that it may call to stop consumption of new runes. It must pass the next state function to stop.

After constructing the rune function, parseInt finally calls forRunes which does the work of consuming runes from the Reader and calling the rune function.

Now let's see that rune function again and break it down. Remember that it is called for every single rune and again at EOF.

parseRune := func(c rune, eof bool, stop func(next stateFunc)) {

if eof {

stop(nil)

return

}

if !isDigit(c) {

r.UnreadRune()

stop(parse)

return

}

buf.WriteRune(c)

}

If EOF has been reached, it calls stop with nil to stop the state machine's loop.

If anything except a digit has been consumed, it calls UnreadRune to put the rune back into the Reader's buffer. Then it calls stop with parse, switching the state machine back into normal mode.

Finally, when a digit has been consumed, it is put into parseInt's internal buffer.

After executing our rune function, forRunes will consume the next rune and call the rune function again (unless stop has been called.)

Now, the state "parse an integer" in the state machine has the actual name parseInt.

To parse strings, we make use of forRunes and rune functions again:

func parse(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

// ... omitted ...

switch c {

case '+':

return parseOp(Plus, "+")

case '-':

return parseOp(Minus, "-")

case '"':

return parseString

}

return skip

}

func parseString(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

if _, _, err := r.ReadRune(); err != nil {

return parseError(err)

}

buf := strings.Builder{}

defer emitBuffer(ch, String, &buf)

parseRune := func(c rune, eof bool, stop func(next stateFunc)) {

if eof {

stop(parseError(errors.New("string not closed")))

return

}

if c == '"' {

stop(parse)

return

}

buf.WriteRune(c)

}

return forRunes(r, parseRune)

}

parseString basically works like parseInt, with some minor differences:

The very first rune is consumed and ignored. It must be the opening double quote of the string. The rune function calls stop when a double quote rune has been consumed. If EOF is reached, this must mean that a string was not closed using double quotes, so it calls stop using parseError.

func parseError(err error) stateFunc {

return func(r *bufio.Reader, ch chan<- Token) stateFunc {

panic(err)

}

}

parseError is a constructor function that returns a parameterized state function. In this case, such a state function will just panic with that error.

This may seem a bit redundant, but it makes future expansion possible in order to also send parse errors into output channels. In addition, there is now a single named function to handle errors.

The state "parse a string" in the state machine now has the actual name parseString.

And with that, our functional approach to the state machine is complete.

Let’s take a step back and revisit the problems using the traditional approach, and how the functional approach solves these issues.

defer statements to do work when processing of a single state is complete.You might wonder what the implications are for the performance of such a functional approach to a state machine. In my experience, it is quite a bit slower (dependent on GC settings.) However, I do think that in terms of clarity of code and therefore maintenance costs, it is well worth using this approach. As the Go proverb says: "Clear is better than clever."

Russ Cox (2023). Storing Data in Control Flow.